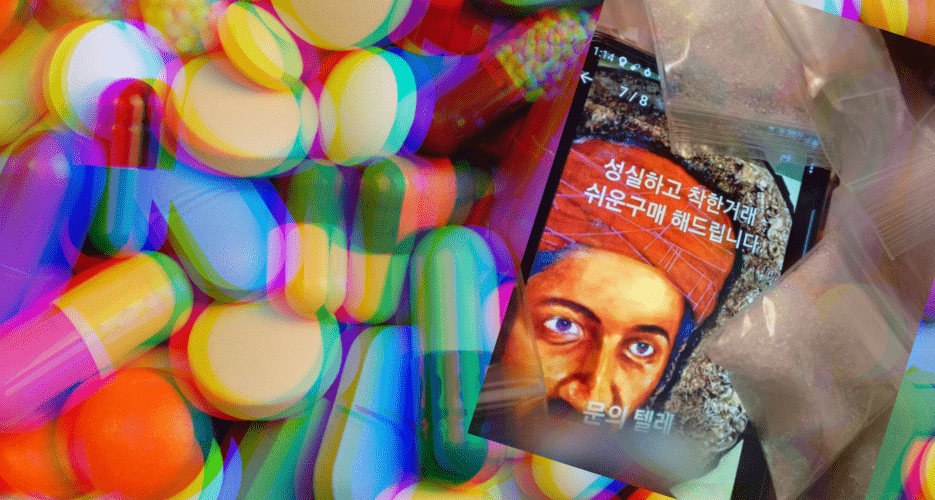

Country needs a serious drug policy, but current measures ignore factors that likely drive Korean use of meth and opiods

Lee was in his twenties when he first experimented with drugs, trying marijuana and cocaine while studying abroad in the U.S. But he says that when he returned to South Korea, he started using “stronger” stuff.

“At first, it was occasional. But once a month became once a week… and then I started using every day. I wanted to quit, but I just couldn’t stop,” said Lee, a pseudonym he uses as a recovering addict in Narcotics Anonymous. “Then one day, I was arrested.”

Lee was in his twenties when he first experimented with drugs, trying marijuana and cocaine while studying abroad in the U.S. But he says that when he returned to South Korea, he started using “stronger” stuff.

“At first, it was occasional. But once a month became once a week… and then I started using every day. I wanted to quit, but I just couldn’t stop,” said Lee, a pseudonym he uses as a recovering addict in Narcotics Anonymous. “Then one day, I was arrested.”

Get your

KoreaPro

subscription today!

Unlock article access by becoming a KOREA PRO member today!

Unlock your access

to all our features.

Standard Annual plan includes:

-

Receive full archive access, full suite of newsletter products

-

Month in Review via email and the KOREA PRO website

-

Exclusive invites and priority access to member events

-

One year of access to NK News and NK News podcast

There are three plans available:

Lite, Standard and

Premium.

Explore which would be

the best one for you.

Explore membership options

© Korea Risk Group. All rights reserved.

No part of this content may be reproduced, distributed, or used for

commercial purposes without prior written permission from Korea Risk

Group.