Many young people who move to countryside for better life end up returning to city due to lack of government support

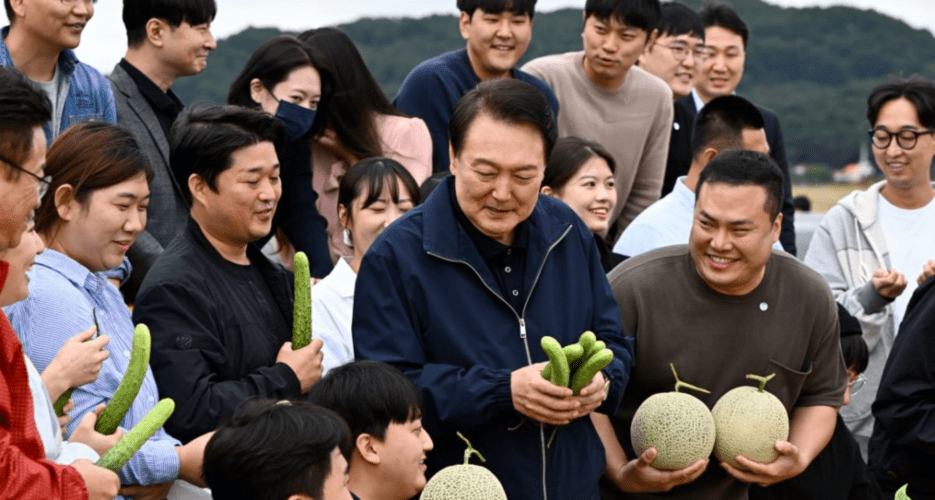

In South Korea, a trend known as “gwinong” signifies a shift from urban to rural living, driven by individuals seeking a departure from fast-paced city life. However, this transition often confronts newcomers with the realities of rural economics and agriculture’s inherent challenges.

Hwang’s case illustrates this trend. After moving to the countryside with his wife to engage in farming, he quickly encountered the direct impact of national policy changes on his agricultural business.

In South Korea, a trend known as “gwinong” signifies a shift from urban to rural living, driven by individuals seeking a departure from fast-paced city life. However, this transition often confronts newcomers with the realities of rural economics and agriculture’s inherent challenges.

Hwang’s case illustrates this trend. After moving to the countryside with his wife to engage in farming, he quickly encountered the direct impact of national policy changes on his agricultural business.

Get your

KoreaPro

subscription today!

Unlock article access by becoming a KOREA PRO member today!

Unlock your access

to all our features.

Standard Annual plan includes:

-

Receive full archive access, full suite of newsletter products

-

Month in Review via email and the KOREA PRO website

-

Exclusive invites and priority access to member events

-

One year of access to NK News and NK News podcast

There are three plans available:

Lite, Standard and

Premium.

Explore which would be

the best one for you.

Explore membership options

© Korea Risk Group. All rights reserved.

No part of this content may be reproduced, distributed, or used for

commercial purposes without prior written permission from Korea Risk

Group.