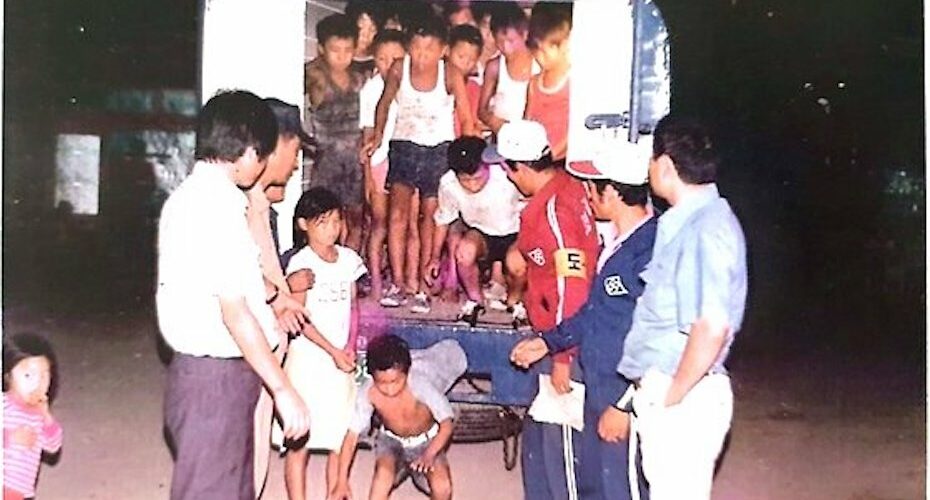

Investigation into rape and torture at welfare center decades ago underlines need to confront continuing abuse today

Ever since its transition to democratic governance, South Korea has had to reckon with the complicated legacy of its post-war dictatorship.

This has included various transitional justice commissions that have investigated decades of violence and human rights abuses, including massacres, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. One of these truth-seeking efforts resumed a little more than two years ago, when the Moon Jae-in administration relaunched the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea (TRCK) in Dec. 2020.

Ever since its transition to democratic governance, South Korea has had to reckon with the complicated legacy of its post-war dictatorship.

This has included various transitional justice commissions that have investigated decades of violence and human rights abuses, including massacres, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. One of these truth-seeking efforts resumed a little more than two years ago, when the Moon Jae-in administration relaunched the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea (TRCK) in Dec. 2020.

Get your

KoreaPro

subscription today!

Unlock article access by becoming a KOREA PRO member today!

Unlock your access

to all our features.

Standard Annual plan includes:

-

Receive full archive access, full suite of newsletter products

-

Month in Review via email and the KOREA PRO website

-

Exclusive invites and priority access to member events

-

One year of access to NK News and NK News podcast

There are three plans available:

Lite, Standard and

Premium.

Explore which would be

the best one for you.

Explore membership options

© Korea Risk Group. All rights reserved.

No part of this content may be reproduced, distributed, or used for

commercial purposes without prior written permission from Korea Risk

Group.